May's bracelet is latest example of the appropriation of Frida Kahlo

9 October 2017

Fionna Barber argues that the Prime Minister's fashion choice is part of a trend commodifying Kahlo's image

by Fionna Barber, Reader in Art History at Manchester School of Art, Manchester Metropolitan University

Like many people, I was somewhat bemused by Theresa May’s Frida Kahlo bracelet. Not only that a British Tory Prime Minister would actually own such a piece of costume jewellery, but that she would choose to wear it during her address to the Conservative Party Conference here in Manchester.

This was the speech that was intended to restore May’s humanity by emphasising the difficulties she’d overcome during her own personal and political journey. However the carefully staged performance soon descended into farce with the delivery of a fake P45 and backdrop malfunctions compounded by May’s evident struggle with a heavy cold.

Sipping from a glass of water, it became obvious that on her wrist was a heavy bracelet made up of self-portraits of the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. The bracelet had clearly been intended to play a role in May’s visible reconstruction of her own identity. Instead it became one further, incongruous element in its disintegration, as all the components of spectacle dissolved into their constituent parts.

There has been much media speculation (including social media) as to why Theresa May would align herself with the posthumous image of a Communist, bisexual artist who was also a disabled woman of colour.

Latest in a trend

However the wearing and visible display of the bracelet was just the latest instance of an established process of the appropriation and commodification of Kahlo’s image.

Kahlo’s art- and the deep fascination with her own image that became the subject of her self-portraits – emerged through the constant renegotiation of the circumstances of her life.

After contracting polio as a child she then suffered a crippling accident that crushed her pelvis and meant that she could never have children. She was in constant pain from her many operations until her death in 1954, yet she also married the Mexican muralist painter Diego Rivera (twice) and had a series of high profile affairs with both male and female lovers, including both Leon Trotsky and Josephine Baker.

If you go on Amazon, a quick search will reveal over a hundred Kahlo-related artefacts for sale – t-shirts, candles and indeed bracelets mostly featuring her iconic heavy-browed image. Much of this merchandise refigures her race as exoticism and recasts the struggles of her life as romantic tragedy. How did this happen?

After nearly two decades of neglect, Frida Kahlo’s remarkable work came to light again as part of the great rediscovery and recuperation of ‘forgotten’ women artists that accompanied the emergence of feminist art history in the 1970s.

An exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1982 paired her with the equally overlooked Tina Modotti, an Italian photographer also working in Mexico in the 1930s and also a member of the Communist Party.

In addition to introducing their work to a wider audience the Whitechapel exhibition took care to emphasise the work of both Kahlo and Modotti as inherently bound up with the wider struggles of contemporary politics.

Appropriation of style

Yet this visibility was also double-edged. As the class politics that Kahlo herself had espoused faded from view during the 1980s her image cast loose from its leftwing moorings and drifted into the marketplace where it has remained ever since. Her apparent exoticism and the narrative of her suffering were ripe for appropriation; by the end of the decade her ‘Mexican peasant style’ was also beginning to feature in fashion shoots. The value of her paintings increased far beyond that during her lifetime, her fashionability also reinforced by the knowledge that Madonna was a collector of Kahlo’s works.

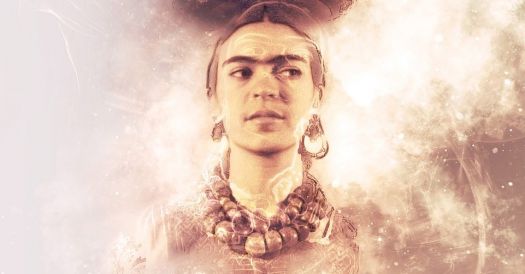

Kahlo herself was completely aware of the importance of dress within the construction of her own image – and that this was always highly political. She posed in self-portraits and photographs in Tehuana costume, bedecked in heavy necklaces and bracelets.

Yet Kahlo’s adoption of traditional dress was firmly identified with Mexican resistance to American imperialism, perhaps nowhere more apparent than in a painting she made during a prolonged visit to New York with Rivera. ‘’My Dress Hangs There’ (1933) presents a radically different view of the Manhattan skyline from that popularised by contemporary male photographers such as Alfred Stieglitz or Paul Strand – or indeed the painter Georgia O’Keefe. Against the backdrop of the modern city, Kahlo painted a washing line on which her Tehuana dress is pinned out to dry, defiantly stating her Mexicanness in the face of everything that New York represented.

Kahlo’s art- and the deep fascination with her own image that became the subject of her self-portraits – emerged through the constant renegotiation of the circumstances of her life.

A colleague of mine has speculated that May’s choice of a Mexican bracelet could also have a meaning in terms of her shifting view on contemporary American politics, indicative of a move to visibly distance herself from Trump’s recent policies despite her initial support at the time of his inauguration.

In the end though we both agreed that this degree of semiotic subtlety on May’s part is a bit improbable. I think it more likely that she was attempting to appropriate some of Kahlo’s aura of survival through suffering as part of a re-imagining of herself as a new icon of Tory femininity, as strong, fierce and yet vulnerable – an aim that has, in the end, horribly backfired.